Hnefatafl, meaning King’s Table (or literally, Fist Board Game) in Old Norse, is an asymmetric game of pure strategy played by the Vikings and neighboring people with many variations. Its origins are unclear, but it seems that it has appeared during the Viking period, in the 7th or 8th century CE, in Scandinavia and other lands which the Vikings have conquered, as accounted for in archaeological finds of Hnefatafl pieces. Tablut is the most documented variation of Hnefatafl, which has been observed by the Swedish botanist, Carl Linnaeus, during his visit to Lapland (northern Scandinavia) in 1732, among the Saami people. Linnaeus recorded the rules and the shape of the board played by the Saami in his diary, written in Latin, Iter Lapponicum. The diary was translated into English for the first time in 1811 by James Edward Smith, under the title, Lachesis Lapponica: A Tour in Lapland. That translation had many mistakes, including wrong rules for Tablut. Since then there were a few attempts to translate the rules correctly and test them out in Hnefatafl tournaments conducted by Aage Nielsen. The most balanced game resulted from a 2013 (updated in 2015) translation done by a Finnish linguist, Olli Salmi, on his website.

| Tablut 1. Arx regia. Konokis Lappon., cui nullus succedere potest. 2 et 3. Sveci N:r 9 cum rege et eorum loca s. stationes. 4. Muscovitarum stationes omnes in prima aggressione depictæ. 0. Vacua loca occupare cuique licitum, etiam Regi, idem valet de locis characterisatis praeter arcem.Leges 1. Alla få occupera och mutare loca per lineam rectam, non vero transversam, ut a ad c non vero a ad e. 2. Nulli licitum sit locum per lineam rectam alium supersalire, occupare, ut a b ad m, alio aliqvo in i constituto. 3. Si Rex occuparet locum b et nullus in e, i et m positus esset, possit exire, nisi mox muscovita aliqvod ex locis nominatis occupat, et Regi exitum præcludit. 4. Si Rex tali modo exit, est praelium finitum. 5. Si Rex in e collocaretur, nec ullus s. ejus s. hostis miles esset in f g sive i m, tum aditus non potest claudi. 6. Ut Rex aditum apertum vidit, clamet Raichi, si duæ viæ apertæ sunt tuichu. 7. Licitum est loca dissita occupare per lineam rectam, ut a c ad n, nullo intercludente. 8. Svecus et muscovita in gressibus alternant. 9. Si qvis hostem 1 inter 2 sibi hostes collocare possit, est occisus et ejici debet, etiam Rex. 10. Si Rex in arce 1 et hostes in 3bus ex N:r 2, tum abire potest per qvartum, et si ejus in 4to locum occupare potest, si ita cinctus et miles in 3 collocatur, est inter regem et militem qvi stat occisus, si qvatuor hostes in 2, tum rex captus est. 11. Si Rex in 2, tum hostes 3, sc. in a α et 3 erint, si capiatur. 12. Rege capto vel intercluso finitur bellum et victor retinet svecos, devictus muscovitas et ludus incipiatur. 13. Muscovitas sine rege erint, suntque 16 in 4 phalangibus disponendis. 14. Arx potest intercludere, æque ac trio[tertio?], ut si miles in 2 et hostis in 3 est, occiditur. | Board 1. The fort of the king (gånågis in Saami), which nobody can enter. “Succedere” with dative seems to mean “enter”. Gånågis means ‘king’. It’s unlikely that it refers to the central square. Fries: “Konokis in Saami, which [i.e. the King] nobody can replace.” The word Lapp is not politically correct nowadays, so I use “Saami” in order not to get blame for Linnaeus’s use of words. I use the Finnish spelling that Sámi giellatekno uses in English. 2 & 3. Swedes, 9 of them with the king and their squares or positions. Fries thinks that number 9 refers to the squares only. 4. The positions of the Muscovites at the beginning of the attack. 0. Empty squares can be occupied by any piece, also the King. This also applies to the specially marked squares except the fort. “Praeter” means “in front of”, but it can also mean “except” (Cartier’s suggestion), which is very precise in the context. Linnaeus could have used numbers but this is shorter.Rules 1. Any piece may occupy a square and move from one square to another in a straight line but not diagonally, as from a to c, but not from a to e. “Alla få occupera och”, Swedish, “all can occupy and”. 2. It is not allowed to pass over any other piece that may be in the way, or to move into its place, for instance, from b to m, in case any were stationed at i or somewhere else(?). “Constituto” participle “placed”. “Alio aliquo” is “anyone else”, or “any other one”, suggesteed by Ahston’s professional translator. 3. If the king should stand in b, and no other piece in e, i, or m, he may escape by that road, unless one of the Muscovites immediately gets possession of one of the squares in question, so as to interrupt him. 4. If the king be able to accomplish this, the contest is at an end. 5. If the king happens to be in e, and none of his own people or his enemies either in f or g, i or m, his exit cannot be prevented. 6. Whenever the king perceives that a passage is free, he must call out rájgge ‘hole’ and if there be two ways open, dujgu ‘hither and thither’. Fries: “tuichu Luule Saami tuoiku ‘up there in front, that way forward’ (Grundstöm, s. 1255f)”. Wiklund’s Lule-Lappisches Wörterbuch has the form tuiku (dujgu in the present official orthography), which is prolative plural, ‘through those [holes]’. Perhaps best translated as ‘this way and that’. 7. It is allowable to move ever so far at once, in a right line, if the squares in the way be vacant, as from c to n. 8. The Swedes and the Muscovites take it by turns to move. 9. If a player can move so that the enemy is between two of his pieces, it is killed and taken off, likewise the king. “Possit” present subjunctive, “be able to”. Literally: “If somebody can move [so that] a piece [ends up] between two hostile pieces,…” Linnaeus had trouble finding a concise formulation of this rule. A suicide interpretation probably makes the game impossible. Fries translates literally. et si ejus in 4to locum occupare potest, si ita cinctus et miles in 3 collocatur, est inter regem et militem qvi stat occisus, si qvatuor hostes in 2, tum rex captus est. 10. If the king, being in his own square or castle, is encompassed on three sides by his enemies, one of them standing in each of three of the squares numbered 2, he may move away by the fourth. If one of his own people happens to be in this fourth square, and one of his enemies in number 3 next to it, the soldier thus enclosed between his king and the enemy is killed. If four of the enemy gain possession of the four squares marked 2, thus enclosing the king, he becomes their prisoner. 11. If the king be in 2, with an enemy in each of the adjoining squares, a, α and 3, he is likewise taken. 12. When the king is taken or imprisoned, the war is over, and the winner takes the Swedes, the loser the Muscovites, and the play starts all over. This rule says nothing about the case of the Swedes winning. 13. The Muscovites have no King and the 16 pieces are deployed in 4 units. 14. The fort can block, as a third [piece], so if there is a soldier in 2 and enemy in 3, it is killed. Tertio is Ashton’s suggestion. Fries: “Trio ‘ox’ seems to be taken from some game where the “ox” is surrounded.” |

There are no original surviving complete sets of Tablut with pieces and board together that have been found archaeologically, although there have been various finds of Hnefatafl pieces and boards, which are not specific to a particular variant.

Since Olli Salmi’s reconstruction of Linnaeus’ Tablut rules results in the most balanced game, I have documented those rules here.

Olli Salmi’s Tablut Rules:

- The game is for 2 players.

- The board is a square with a 9×9 grid. There are 25 pieces total: 16 attackers (Moscovites), 8 defenders (Swedes), and 1 king. The first player plays for the attackers. The second player plays for the defenders and the king.

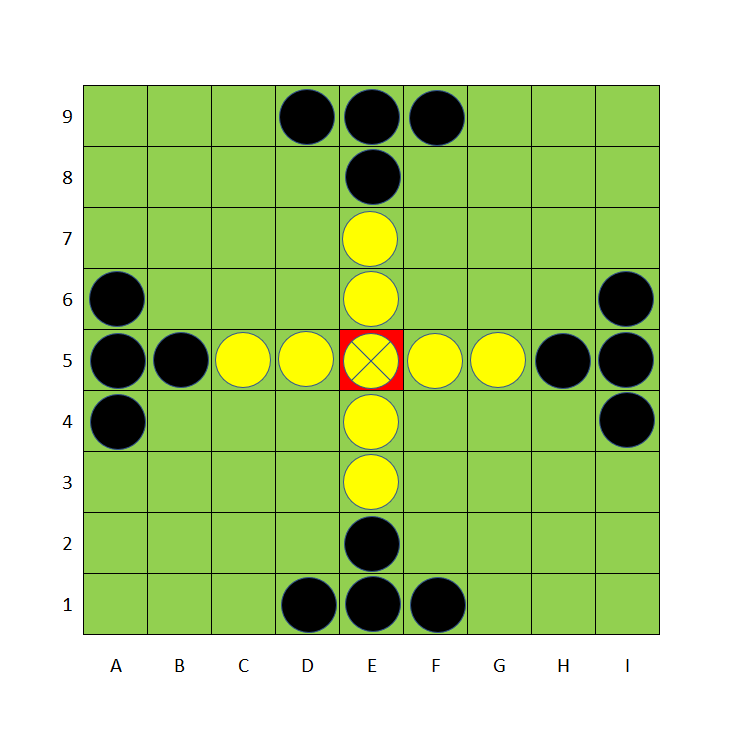

- The initial position of the pieces is shown in the following diagram. The king is placed on the throne. The defenders surround him in the shape of a cross. The attackers are placed on four sides in T shaped groups.

- The central square, called the throne, may only be occupied by the king. The king can go in and out of the throne at any time. Other pieces may pass through the throne when it is empty but are not allowed to land on it. The throne square is hostile to both the attackers and defenders, meaning that when it is empty it can replace one of the two pieces taking part in a capture.

- The attackers move first. The two players alternate their moves.

- All pieces, including the king, move any number of vacant squares along a row or a column, like a rook in chess.

On Strategy:

- According to the rules presented above, the balance of Tablut between the attackers and the defenders is similar to the balance of chess. In chess, since whites go first they have about 52-59% of winning compared to the black, as has been documented in many different tournament statistical analyses. Aage Nielsen documented based on tournament results, that Tablut is -1.11 balanced on average, meaning that the attackers win about 10% more often. In other words, the attackers win in Tablut 60% of the time, compared to 52-59% of the white in chess.

- Since Hnefatafl is asymmetrical, each of the players must use a different strategy to win.

- The attackers need to form a blockade around the defenders so that the king gets surrounded and eventually eliminated. As long as the ring around the king remains unbroken he cannot escape. The blockade is formed by positioning the attackers in the shape of a rhombus on a diagonal of each row. Once the blockade is formed attackers need to slowly make the rhombus smaller and smaller around the center of the board and tighten the noose around the king.

- The goal for the defenders is to constantly create gaps in the blockade and have the king escape through one of those gaps to the edge of the board. Placing defenders behind the enemy lines makes it much easier for them to eliminate more attackers and break through the blockade.

- Some chess tactics are also applicable in Hnefatafl. Forcing the opponent to make a particular move to avoid losing the game can be very useful. Creating a fork where one piece can attack multiple opponent’s pieces can provide an advantage. Pinning a piece, which prevents it from being moved from its location by the threat of losing the game, is another useful tactic that gives the player control of the board.

Bibliography: